Is reading prioritised in primary schools?

Maybe, maybe not.

The publication of the oracy strategy in England earlier this year prompted excellent blogs and widespread comment on social media (at least, on my bit of it!). One of the common remarks was to the effect that primary schools prioritised reading and writing over oracy. “No,” chimed in some literacy specialists, “reading is prioritised over writing and oracy”. That’s likely true and it’s a good thing too. Reading is simply the most important piece of the three both in daily life and continuing education and I would argue that a crucial part of primary school is teaching children to read well. That said, I have a suspicion that primary schools are not always teaching reading as effectively as they could and the missing element is reading fluency – a crucial bridge between the phonics tested in KS1 and the comprehension tested at the end of KS2.

Thinking back to my PGCE, we had plenty on the importance of phonics, a check on accuracy of reading via reading records and also lots of interesting discussions on the usefulness of picture books and the need to encourage reading for pleasure. However, I don’t think we studied anything seriously on reading fluency and neither did my placement schools draw it to my attention. Perhaps this is not surprising because reading fluency is barely mentioned in the National Curriculum either.[1] However, in my first year as an ECT in Year 4, it became clear that whilst nearly all of my class had mastered phonics fairly well, there were many who couldn’t read fluently.[2] At some point during that year, I read The Art and Science of Teaching Primary Reading by Christopher Such and was blown away by what I had been missing. In particular, Chapter 5 on fluency made me realise the importance of this element of reading as a bridge from phonics to children enjoying their reading.

In the last few weeks, there have been 2 important pieces of research published on children's reading. The one that gathered all the media attention was the National Literacy Trust’s Annual Literacy Survey showed that the percentage of children who said that they enjoyed reading had dropped to the lowest level since the survey started in 2005. This rightly caused a lot of soul searching about what is definitely an unwelcome trend given the clear links between reading enjoyment and academic success. A lot of the speculation as to the reasons why seemed dubious especially those focusing on curriculum since this isn’t limited to England - see here for discussion of similar trends in the USA.

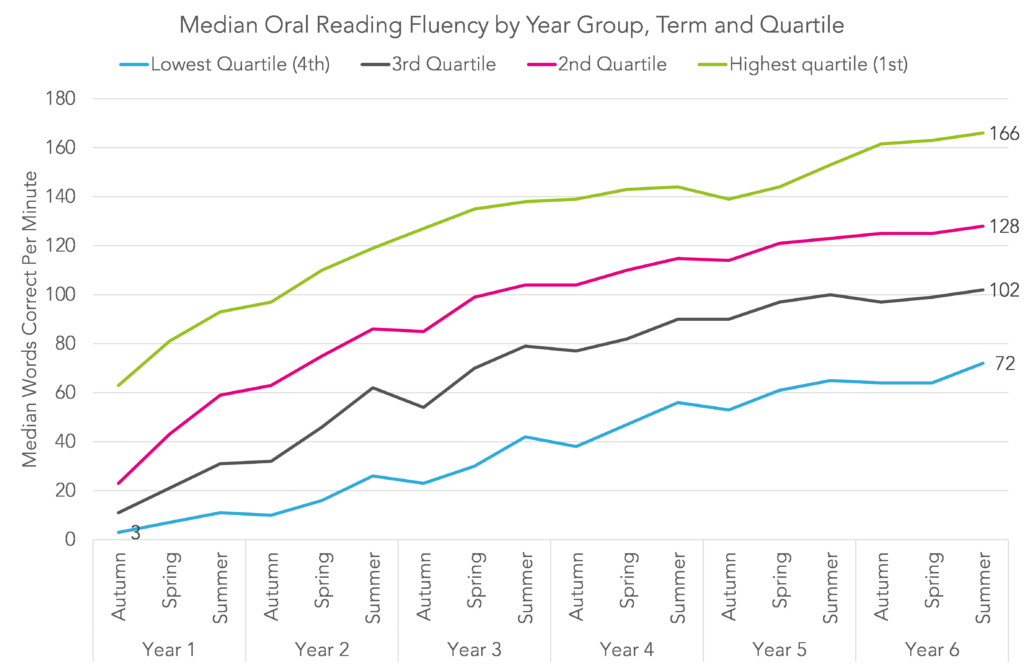

Also published, to considerably less media attention, was data from FFT Education Data Lab’s Reading Assessment Programme (“RAP”) on reading fluency. This showed that the average fluency of the children taking the RAP at the end of Year 6 was 114 words a minute. However, this headline figure does not give the whole story of the huge range in fluency. Split into quartiles, the averages looked like this.

This prompts the obvious question – what level of reading fluency should children have by the end of primary school? There doesn’t seem to be a straightforward answer to this question. However, it seems clear that below a certain level, reading fluency clearly impacts comprehension because so much of the reader’s attention is devoted to simply reading the words. In the Art and Science of Primary Reading, Christopher Such suggests that this level is likely to be around 110 WPM, a figure that FFT endorse in their report, noting that accuracy and prosody are also required.

Since the RAP is a programme that schools have to sign up to and the reading fluency assessment is entirely optional, the cohorts taking these assessments are at schools may well have more focus on reading fluency than the average. Accordingly, it is unlikely that these figures will be understating the overall level of reading fluency in England’s schools. They may be overstating them somewhat.

If we accept 110 WPM as a rough benchmark for fluency and assume that the RAP results are representative (or better) than England’s schools as a whole, then close to 50% of pupils are leaving primary school dysfluent. Unsurprisingly, this lack of fluency affects results in KS2 reading comprehension SATs. FFT found that approximately half the gap between girls and boys and between disadvantaged and not disadvantaged pupils here can be explained by the differences in reading fluency.

However, the problems go well beyond an exam taken at the end of primary school. Every single subject in secondary school is going to required reading to some extent. To what extent are secondary schools aware of this as problem and how many are set up well to develop reading fluency? I don’t claim any expertise on this but it feels to me like something which might often be neglected because it isn’t clearly anyone’s responsibility.

This brings us back to reading for pleasure. In their They Behave For Me podcast, Adam Boxer and Amy Forrester discussed how “reading for pleasure” is a bit of a misnomer because it isn’t reading itself which brings pleasure but reading things that you are interested in or entertain you. True enough but reading fluently is probably close to a necessary condition for enjoying reading anything at all (at least outside graphic novels).[3] I got a certain grim satisfaction in plodding through the original German of the The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum during my A Level but I certainly couldn’t describe the experience as enjoyable.[4]

So while the steady drop in children reading for pleasure is likely caused mainly by wider societal changes, there must be some benefit in trying to increase the pool of children able to enjoy reading by ensuring that the vast majority leave primary school able to read fluently. It seems that we are still some way from that goal. Achieving near universal fluency would also likely boost reading comprehension much more effectively than the fruitless attempts to teach “inference” skills and the like.

If you are convinced by this argument, you may be wondering what exactly you should be doing to develop reading fluency. Again, on this, I would refer you to Christopher Such’s book and his blog, Primary Colour, where he goes into more detail on developing fluency and also gives some further reading. What worked for me was continuing to regularly read aloud as a class but adding in regular short sessions of paired oral reading where a short passage is read and then re-read in mixed-attainment pairs. A potentially tricky part of a novel you are reading, relevant non-fiction and poetry all work really well for this. In terms of monitoring your children’s fluency, you could obviously use the RAP but if your school doesn’t subscribe, the materials from DIBELS also work well coupled with some teacher judgment on prosody.

In short, I am passionate about children reading for pleasure but no amount of wonderful displays and passionate teachers are going to do it if children are functionally dysfluent. The range of children’s books out there are better than they have ever been. We need to make sure that all children have the opportunity to enjoy them.

[1] There are some references to fluency of word reading in connection with phonics but other than that there is a single reference in Year 5 and 6 stating that, “Pupils’ knowledge of language, gained from stories, plays, poetry, non-fiction and textbooks, will support their increasing fluency as readers.” Not very helpful.

[2] My school had a strong emphasis on teachers and TAs reading one to one with children and I also did a lot of FASE Reading (as described in Teach Like a Champion). Both of these flagged up the lack of fluency.

[3] I found zero research on this point. Let me know if there is any.

[4] I realise that reading a foreign language novel isn’t a perfect analogy for not being fluent in reading a book in one’s native language but it is probably the closet that a literate adult can get to the feeling of being dysfluent.

Hi Mark, excellent article - like writing, I think a lot of reading instruction is just 'get them reading' as though that's enough. It should be more explicit if we want to see real progress.

There is a four-part reading fluency rubric that we've used for a couple of years in our school but the language is quite 'grown-up' so one of my colleagues (the school English lead) made a more child-friendly version. Would you like me to send you it? It might be something to use, write about or both if you like it (or ignore if you don't!).